The TSP’s New Spillover Methodology for 2021

Beginning with the first full pay period of 2021, the TSP is dramatically changing the way that it processes Catch-Up contributions. The new method includes both Civilian and Uniformed Services participants. If you are paid by the National Finance Center, the spillover methodology will be effective PP26, as that’s the pay period associated with the first pay date in 2021.

Let’s start by talking about what’s not changing. If you will be under age 50 by December 31, 2021, then you will not be immediately impacted by this change because you will not be eligible to make Catch-Up contributions in 2021. Your relationship with the TSP is the same for now, and when you hit your 50th year of birth, you will become eligible for Catch-Up contributions and will follow the new spillover methodology described below.

The analysis here is based upon the following TSP Bulletins:

I believe following analysis to be accurate, but I defer to the TSP bulletins above and the TSP itself as the final word on the implementation of the new spillover methodology.

For you folks that are not yet eligible for Catch-Up contributions, I again urge you to stop using a percentage of your pay as a basis for making a TSP contribution. Please use a stated dollar amount. Don’t use 15% of your pay, for example, see what that is in dollars by looking at your payroll statement and switch to that dollar amount. If it’s under $750 per pay period, then start increasing your TSP contribution every pay period, even if only by $5 a pay period. Have a plan to max out the allowable contribution. The only folks that should be using a percentage basis for their contribution are folks that are just looking for the full government match on the first 5% of contributions. These are usually folks that are just starting out or folks that are saving through a spouse’s plan or a non-employer plan.

The new spillover methodology discussed in the following paragraphs still does not fix the issue of reaching the maximum deferral amount before year end. If you are making $170,300 per year, or $6,550 per pay period, and you elect to contribute 15% to the TSP, that’s a contribution of $983 per pay period. If you contribute $983 for 26 pay periods, that’s $25,558 annually, well above the 2021 limit of $19,500. If you were to make this mistake in 2021, at $983 per pay period, you’d hit the maximum TSP contribution of $19,500 after 20 pay periods (19.84 pay periods, but rounding to 20.) That means that you will miss out on your 4% matching for 6 pay periods, so that’s $6,550 x 4% x 6 = $1,572 in missed matching from the government because you were using a percentage multiplier that was too large. If you want to max out the TSP contribution, do not play games with percentages – just elect $750 per pay period. It’s as simple as that. I get the emails – this happens quite frequently to folks that are using percentages.

For you folks that are eligible for Catch-Up contributions, here’s my analysis of what has changed and how to properly participate in the TSP to get the full benefits of your Regular and Catch-Up contributions. The biggest change is that there is no longer any separate election form or process to elect Catch-Up contributions. The TSP-1-C form has been discontinued. TSP Participants will now just elect an amount per pay period to contribute (percentage or dollars, but I encourage dollars.)

As a refresher, remember that Regular contributions are tax-deferred or tax-advantaged (Roth) and the first 5% you contribute per pay period is matched with 4% by the government. You also receive a 1% automatic contribution from the government, even if you make no TSP contributions, so that’s why it looks like the government matches 5% with 5%, but they are matching 5% with 4% and giving you 1% for having a pulse.

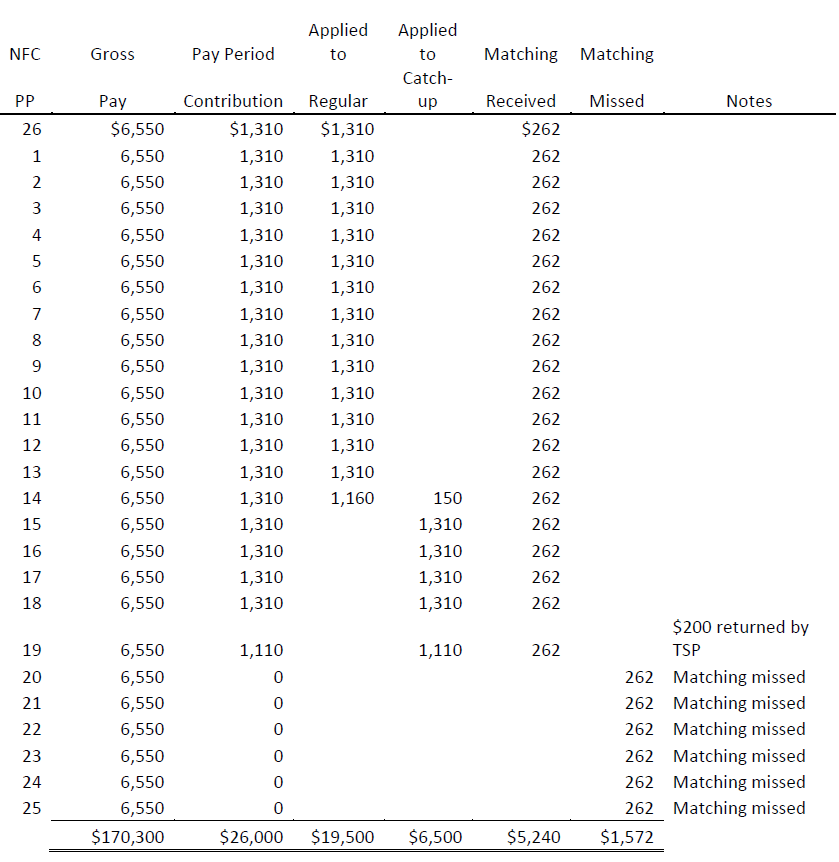

With the new method, it’s even more important to get away from using percentages as a contribution base. The new methodology still will not solve the issue discussed in the section above for folks that are not yet eligible to make Catch-Up contributions. Even with spillover, if you contribute too much, too soon, you can still miss out on matching. Let’s use the same $170,300 per year, which is $6,550 per pay period, but now let’s say the contribution rate was set to 20%. At 20%, that’s a contribution of $1,310 per pay period and $34,060 annually. Even with spillover, this person will have hit the combined maximum deferral of $26,000 in the same 20 pay periods (really 19.84, but I am rounding.) As you can clearly see, spillover does not fix this. You will miss out on the same $1,572 of matching contributions from the government.

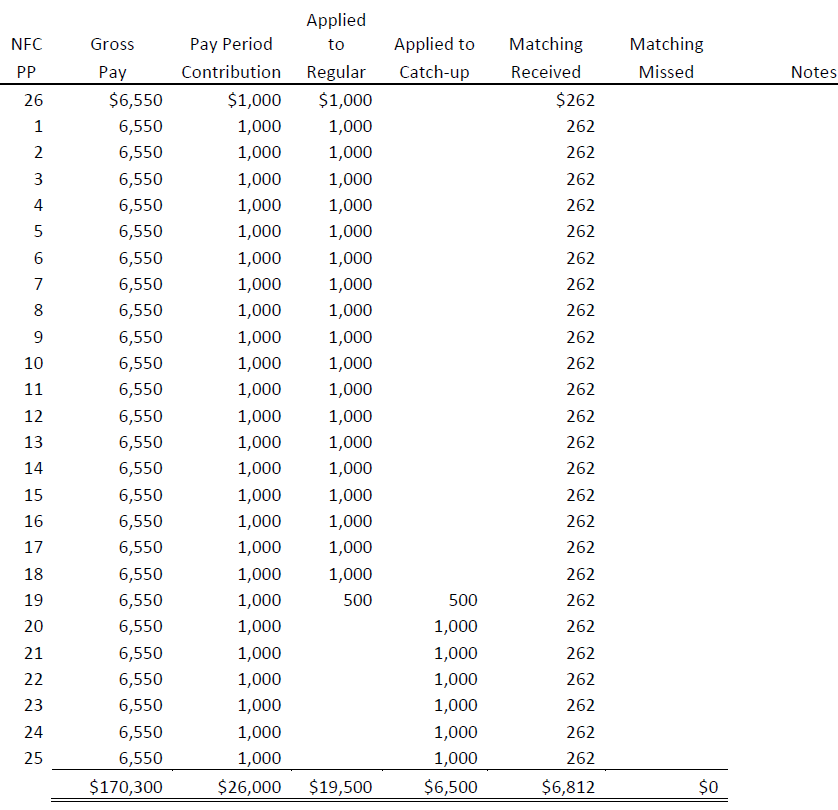

Let’s first examine what happens when an employee gets it right. The maximum deferral for 2021 is $26,000 ($19,500 Regular + $6,500 Catch-Up = $26,000) and we have 26 pay periods in 2021 at the NFC. Can it be any easier? This smart person logs into the Employee Personal Page and elects to have $1,000 contributed per pay period to fully fund the maximum deferral. Here’s how the TSP will handle and classify this contribution scheme:

See how the TSP applies the contribution to the Regular first, and then to the Catch-Up Contribution. No match is lost.

Now, let’s see how the TSP will handle the situation described earlier where the employee errantly has $1,310 per pay period deducted:

As you can see, this person really screwed up. The TSP will apply the $1,310 contribution first to the Regular Contribution until the maximum deferral of $19,500 is reached. After that, all contributions are directed as Catch-Up contributions until that maximum deferral of $6,500 is reached. The extra $200 from pay period 19 is returned to the employing agency for further refund to the employee. This person misses out on $1,572 of matching for the remainder of the year because they didn’t listen. Stop using percentages as a contribution basis for your TSP contributions.

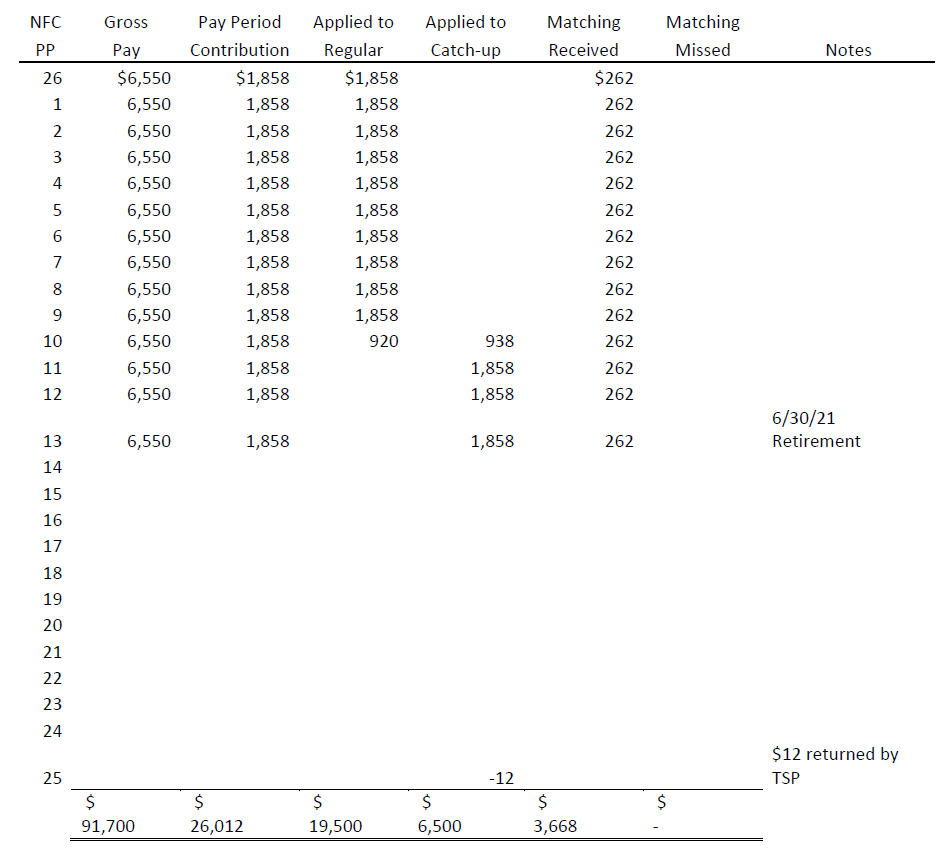

I’ve already had a number of people ask me about what to do if they are planning to retire on a date other than December 31. What about a person that plans to retire on June 30? How can that person ensure that they reach the maximum deferral of $26,000 by the end of pay period 13 at the NFC? That’s easy – $26,000 divided by 14 pay periods is approximately $1,858 per pay period. The chart below demonstrates how the TSP will allocate that $1,858 contribution for 14 pay periods:

Very clean as you can see. Both goals achieved – the Regular Contribution of $19,500 has been met and the Catch-Up Contribution of $6,500 has been met. By rounding up pennies, this person contributed an extra $12 that will be returned by the TSP to the employee’s payroll center for credit back to the employee. Pre-spillover, the TSP would have returned the entire contribution for pay period 13, as that contribution put this person over the deferral limit. Under spillover, the TSP is allowed to accept the contribution up to the maximum deferral limit and just return the overage.

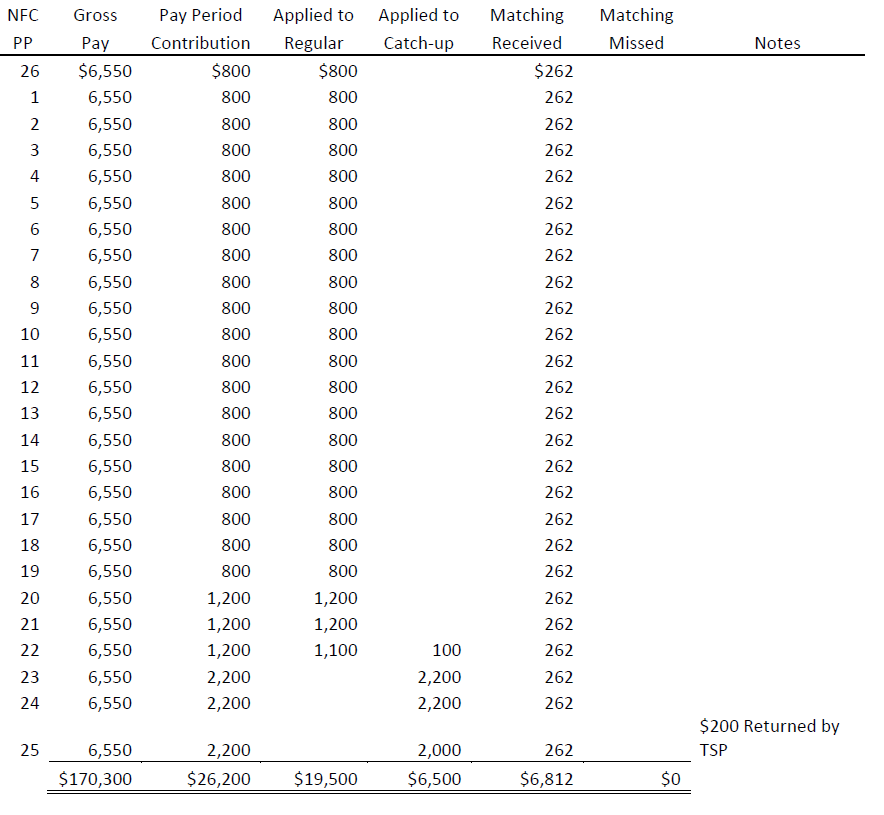

Now, for the next example. Let’s examine what happens when you put no effort into your future and just “guess” at what you should do, and then take corrective actions at the end of the year to remedy the situation. This person just “picks” $800 per pay period as the contribution amount and by pay period 19, this person realizes by talking to his friends that are FERSGUIDE subscribers that he’s on the wrong path. In a panic, this person jumps to $1,200 per pay period for 3 pay periods, then this person becomes a FERSGUIDE member, and emails me for help. This person then adjusts their TSP contribution to $2,200 for the final three pay periods of 2021 and ends up just where they want to be – a full $26,000 deferral and no missed matching. See the chart below.

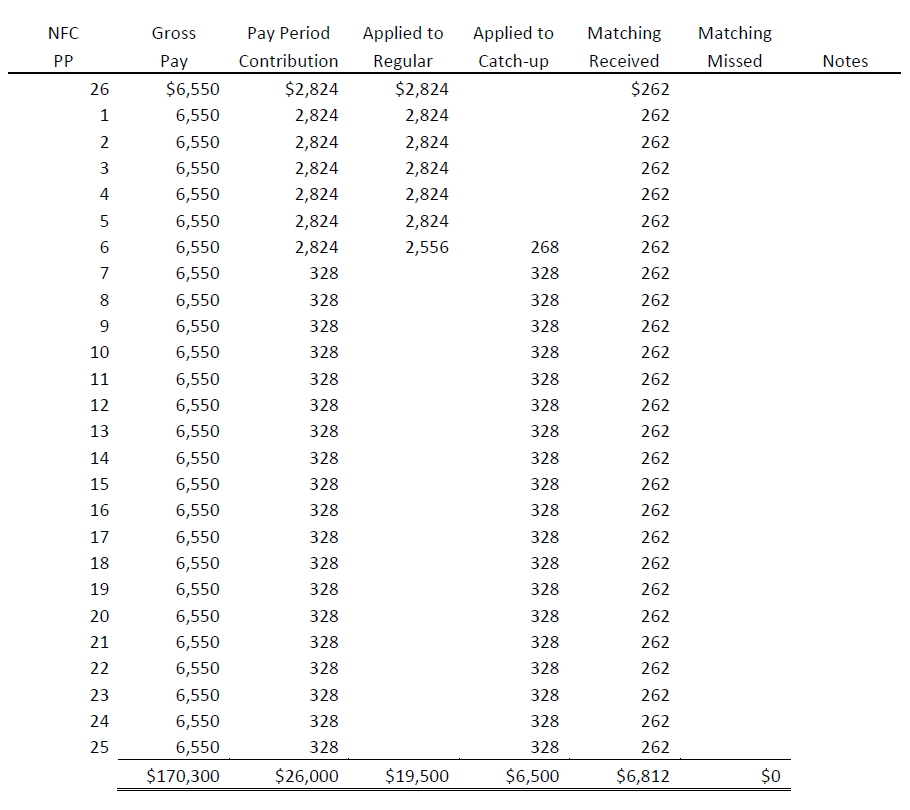

For the final example, let’s see how hard it is to “frontload” the TSP contribution. I have a number of subscribers that tell me that they like to frontload the TSP Catch-Up contributions and would elect to contribute $1,083 per pay period for 6 pay periods ($6,500) and get their Catch-Up contributions into the TSP quickly, so it can go to work for them sooner. That’s one way to look at it – but I prefer dollar cost averaging and spacing it all out evenly, but so many folks currently frontload that I want to demonstrate how to do that. In this example the employee contributes $2,824 per pay period for 7 pay periods and then submits a new election for $328 per pay period for the remaining 19 pay periods.

That is how you frontload under the spillover method. We have achieved our goal of hitting the maximum deferral of $26,000 and did not miss out on any matching because pay periods 7-25 have a contribution of $328, which is 5% of $6,550, giving us the 4% match of $262.

Dan Jamison, CPA. If you are not a FERSGUIDE member and found this information useful, consider subscribing at www.fersguide.com

FedSavvy Educational Solutions takes no responsibility for the current accuracy of this information. Securities offered through J.W. Cole Financial, Inc. (JWC) Member FINRA/SIPC. Advisory Services offered through J.W. Cole Advisors (JWCA). FedSavvy Educational Solutions and JWC/JWCA are unaffiliated entities. Securities are not FDIC insured or guaranteed and may lose value. Investments are not guaranteed and you can lose money. This presentation is for educational purposes only and is not an offer to buy or sell an investment. Neither FedSavvy and JWC/JWCA are tax or legal advisors and this information should not be considered tax or legal advice. Consult with a tax and/or legal advisor for such issues.